By: Jolene Edgar

Seeing an aesthetic procedure all over social media can breed a strange sort of FOMO. (Hey, we’re not immune.) Yet it may be difficult to distinguish for-the-’Gram fads from truly “Worth It” tweaks. Which is why we’re launching a new series on RealSelf: Everybody’s Doing It. Each month, we’ll explore all sides of an of-the-moment cosmetic procedure, to bring you the uncensored truth about its efficacy and safety, so you can decide if it’s right for you. Here, in our first installment, we’re dissecting the buccal fat removal debate.

While I’ve never quite understood society’s gross fascination with pimple-popping content—stomach of steel, that Dr. Sandra Lee—I have found myself recently spellbound by extraction videos of a different variety: buccal fat removal. Anyone who’s witnessed the face-slimming surgery—that moment when glistening yellow fat erupts from the inner cheek—can no doubt relate. And I’m guessing that’s more than a few of you, given the sudden prevalence of these videos on social media. “There’s definitely been an uptick in requests for buccal fat removal,” says Beverly Hills, California, facial plastic surgeon Dr. Sarmela Sunder, who fields upwards of 10 inquires a week about the surgery, primarily from women in their 20s and 30s. The procedure’s popularity has soared in response to a collective quest for a specific face shape, she adds—one with cheekbones strong and wide, a tapered chin and a chiseled jaw.

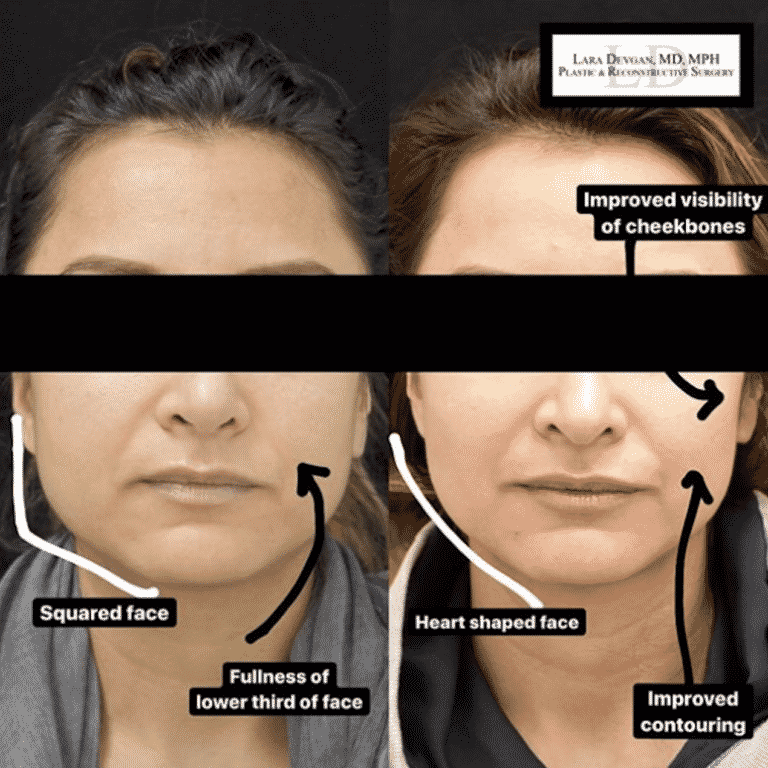

“The whole purpose of the operation is to highlight the bony architecture, giving more definition and angularity to the face,” says New York City plastic surgeon Dr. Alan Matarasso, who was among the first to describe the intraoral buccal fat excision technique in scientific literature. As with contouring makeup, the goal of surgery is to cast a shadow across the mid-cheek hollow, thereby highlighting the cheekbone above and jawline below—only, in this case, to permanent effect. “It simulates the look one has when sucking gently on a straw,” he explains. “When done right, it’s always a subtle change.”

Dr. Matarasso performs the surgery across demographics, he says—“in teenagers who are also having their noses done [slenderizing the cheek can help bring balance], twentysomethings after the model look, and older patients with very full, round faces.” Even men are getting wise to the perks of the procedure. “Fifty percent of my buccal fat consults are guys,” says Dr. Sagar Patel, a facial plastic surgeon in Beverly Hills, California. “The majority are wanting to look more mature and masculine so [that] people at work will take them seriously.” Imagine that—getting plastic surgery because you want to look older.

The buccal fat removal movement is not without dissenters, however—plastic surgeons who deride the rise of such “fad procedures” and fear the long-term consequences of plucking fat from cherubic twentysomethings. But before we weigh the treatment’s reputed benefits against its potential pitfalls, let’s take a closer look at this particular fat pad.

What is buccal fat, and what happens to it with age?

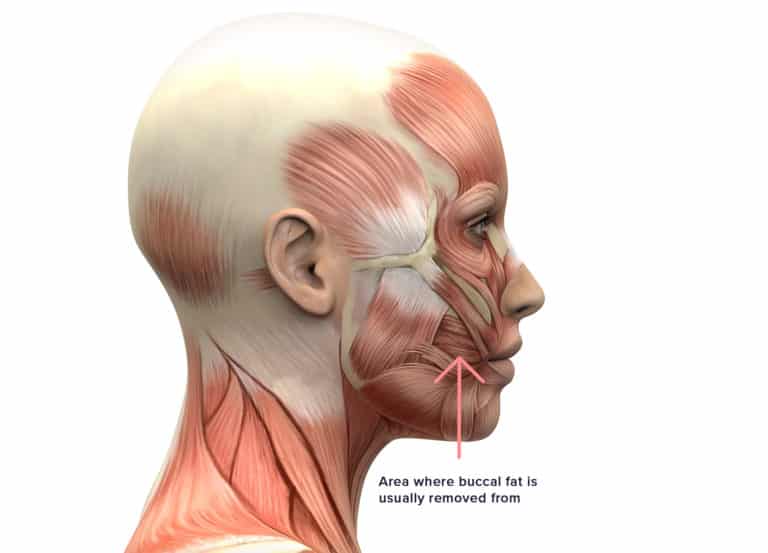

When old ladies pinch babies’ cheeks, they’re usually grabbing hold of buccal fat—that pudgy part by the corners of the mouth. But the buccal fat pad isn’t limited to the lower cheek—it extends back toward the jaw and up into the temples, with some segments embedded deeper than others. It’s sandwiched between two masticatory muscles, where it serves as a sort of gliding pad. In infancy, it facilitates suckling; later in life, it assists in chewing. It also shares space with the parotid duct, which funnels saliva into the mouth, and the facial nerve.

“The buccal branches of the facial nerve, in particular, are intimately associated with the buccal fat pad, so it is in a bit of a danger zone in terms of operating,” notes Dr. Steven Levine, a plastic surgeon in New York City. (Tweaking those nerves could affect your smile and the ability to puff out or suck in your cheeks. “But such injuries are rare, and when they do occur, they usually resolve on their own within three to four months, if not sooner,” he adds.)

While all facial fat shrinks to some extent over time, “the buccal fat, in my experience, tends to maintain relatively well throughout life,” says Dr. Levine, who commonly finds a fair amount even in his 70-year-old facelift patients.

And here’s where things get controversial. The persistence of buccal fat—how much it degrades, how swiftly and how its absence may influence your future face—is a point of debate among experts. According to Dr. Matarasso, “the volume of the buccal fat pad is fairly consistent among all adults, regardless of gender, age and body type, and it doesn’t change much over time.” Several published reports support his position (here and here). One study involving the dissections of six cadavers—all older than 60—found buccal fat pads of “normal weight and volume” even in emaciated specimens.

Dallas plastic surgeon Dr. Rod Rohrich, who has written extensively about the fat compartments of the face, insists that buccal fat does, indeed, diminish with age and that “in most cases, you should not remove it—except in the person with a really full face—because doing so can cause premature aging and midface distortion in the long term.” In his estimation, buccal fat ages faster in men and in folks with genetically thin faces.

While there are many deep and superficial fat compartments contributing to youthful plumpness, “it’s the malar fat pads, or apples of the cheeks, that are the most pleasing and important,” contends Dr. Lara Devgan, a plastic surgeon in New York City and RealSelf’s chief medical editor. As they flatten and fall, many choose to restore them with filler injections or fat grafting. On the contrary, she notes, “it would be rare and exceptional to want added fullness in the buccal sulcus [cheek hollow].”

A 2018 retrospective analysis of buccal fat removal data entitled Buccal Fat Pad Excision: Proceed with Caution makes the point that “buccal fat pad growth is dynamic and drastically increases between the ages of 10–20 … to then decrease over the following 30 years.” The authors also repeatedly acknowledge the lack of “published data regarding the long-term patient follow-up and complications of this procedure”—which makes it impossible to predict how such fat-subtracted faces will fare in the future.

This fact has some surgeons concerned: “If you’re talking about doing this surgery on a 25-year-old looking for that whistle look—I’d advise against that in almost all cases,” says Dr. Levine, who worries about the predictability of the outcome, both now and later. “When you’re taking out buccal fat, it can be hard to judge exactly how much to remove to create enough of a difference without making someone too gaunt.” Regarding the few young patients he’s made exceptions for over the years, he says: “If you were to ask me if I’m worried about [how] those patients [will look] in 20 years… yeah, I guess I am.”

So where does that leave us? Dr. Sunder offers this indisputable takeaway: “There’s definite clinical evidence that the face, on the whole, does become more gaunt over time. To what degree depends on the individual and their ethnicity. But regardless, if you’re removing any fat from the face—whether it’s fat that’s thought to atrophy with age or not—then you’re adding to that phenomenon of facial thinning.”

Related: The Surprising Reason I Tried Cheek Fillers for the First Time

Is buccal fat removal right for you?

If your lower-cheek fullness (aka chipmunk cheeks) bugs you enough to land you in a surgeon’s office, then buccal extraction is certainly worth discussing. Be aware though, it is feasible for a face to be too plump for this procedure: “In about 10% of cases, I have to tell someone their face is too full—usually they’re significantly overweight—and that buccal fat removal is unlikely to show results,” says Dr. Patel. “That’s a pro and a con of this surgery—it gives only a subtle change in almost everyone.”

Doctors will also turn you away if they determine your fullness to be caused by something other than buccal fat. “One of the most common things people mistake for buccal fat is masseter hypertrophy,” says Philadelphia facial plastic surgeon Dr. Jason Bloom, referring to bulky jaw muscles that can result from teeth clenching and grinding. “Those big masseter muscles are further back on the face and can be slimmed down with neuromodulator injections,” he explains. “If someone has both problems, I can Botox the back and take out the buccal fat up front, to sculpt the lower face more completely.” But rashly removing the fat alone could accentuate the heft of the jaw, so make sure your surgeon accurately pinpoints the true source of your discontent.

Age is perhaps the biggest—and most contentious—of disqualifying factors. Certain doctors will hesitate to remove buccal fat on patients in their 20s, or even early 30s, who haven’t naturally leaned out yet. Referring to the aforementioned study showing that buccal fat continues to grow throughout the teens and 20s, Dr. Sunder says, “If we remove it during this period, when it’s expanding, you could look doubly hollowed-out in your 30s or 40s.”

When consulting with young people, she’ll ask to see photos of family members they resemble. If said relatives are gaunt at 40, 50 or 60, she’ll caution patients about removing fat at such an early stage. If they decide to move ahead, she explains, “I’ll take a more conservative approach than I would with someone who’s already reached the potential of her leaning out.” But if they’re obviously chasing a more dramatic effect than the procedure can procure, she’ll refuse to operate, knowing “they’ll likely be displeased with the subtlety of the immediate result—and then they may be unhappy with the long-term outcome, because even a conservative approach can lead to significant hollowing down the line.”

Still, plenty of doctors will acquiesce when it’s clear that someone understands and accepts their uncertain fate. “Patients will say, ‘I don’t care—this is for my career. I need to look my best right now, and if I’m gaunt in the future, I’ll worry about it then,’” says Beverly Hills, California, plastic surgeon Dr. Sheila Nazarian.

And should they later regret that decision? “A little bit of [collagen-building] Sculptra can usually take care of the problem,” says Dr. Nazarian, who also finds that “fat transfer back into the buccal fat pad works really well.” Other surgeons argue that correcting buccal hollowing can actually be quite challenging. “I have patients come in, saying, ‘I had my cheek fat removed years ago, and now I look hollow,’ so we’ll do filler or fat grafting to replace it,” says Dr. Sunder. But because this is a highly dynamic zone and “pretty much the only area of the face where there’s no firm foundation or bone, one can look really done and obvious, if treated poorly.”

Of course, in 15 or 20 years, when buccal-depleted millennials and Gen-Zers are mourning their lost fat, volume-replacement techniques will surely have evolved exponentially. “It’s going to be a totally different game,” says Dr. Patel, “so I really don’t think [long-term hollowing] is an issue.”

What to expect during buccal fat removal surgery and after

Buccal fat extraction is, by all accounts, relatively quick and low-risk in the hands of an experienced board-certified plastic surgeon or facial plastic surgeon. That being said, “if you don’t know what you’re doing, you could be mucking around in a rough area,” notes Dr. Levine. Bleeding and infection are possible complications; nerve injury, as mentioned, is rare and usually temporary.

The procedure can be done in your surgeon’s office or operating room (OR), under all manner of anesthesia, depending on doctor and patient preferences. Some find numbing shots to be sufficient; others combine local with oral or IV sedation; and in the OR, many use general anesthesia.

Once you’re anesthetized, your surgeon will mark a one- to two-centimeter incision line on the inside of your cheek and use a scalpel to slice through the superficial tissue. “The muscle underlying it, I don’t cut, because that can cause too much bleeding,” says Dr. Bloom. Instead, he uses a blunt instrument to vertically dissect through the muscle fibers until he’s met by buccal fat. At this point, your surgeon may have an assistant press on the outside of your cheek while he slowly teases free the fat from inside. “I only take what your body gives me,” says Dr. Patel. “If I tug gently and nothing more comes out, that’s it—I don’t go digging for more.” (Doing so can cause scarring and nerve damage.) Doctors commonly compare the size of the extracted fat wad to that of a walnut or large grape. One or two dissolvable stitches is generally all that’s needed to close the wounds.

The procedure takes 15 to 30 minutes, causing soreness and swelling akin to that of wisdom-tooth extraction. Occasional icing and sleeping with your head elevated should help minimize side effects. Your doctor may limit you to soft foods for the first few days and advise against exercising for up to a week. You’ll have to swish with a prescription mouthwash after meals, to keep your incisions clean.

“It usually takes about two weeks for the majority of the swelling to go down,” says Dr. Nazarian, at which point, your results should gradually start to show. But doctors say it’s highly variable, with some people not noticing complete payoff until three or six months post-op. “There’s a little bit of a shrink-wrap effect at work—you have this empty space after surgery, and it takes a while for the tissues to come back together,” Dr. Sunder explains. “I’ve had patients who are thrilled at three months and then come back at six months, looking even better.”

Buccal-plus: other procedures commonly done with buccal fat removal

While buccal fat removal can certainly be a solo act, in some instances, accompanying procedures can make for a more harmonious outcome. “I don’t think I’ve ever taken out buccal fat as an isolated surgery in young patients—it’s usually done with neck liposuction and/or a chin implant for an overall slimming effect,” Dr. Levine says. In Dr. Matarasso’s office, nose jobs and neck lipo are popular complements to buccal removal, since they work together to “enhance the contour of the face,” he says.

In about half of Dr. Patel’s female buccal patients, he’ll recycle the culled fat once it’s been properly sterilized and filtered. “I usually remove about 4 cc from each side, and I’ll reinject it to give people higher cheekbones, for a more impressive result that lasts,” he says. Likewise, doctors routinely add temporary hyaluronic acid fillers to the tops of the cheeks following buccal extraction, to give the whole of the cheekbones more pop.

In older patients whose skin lacks spring, removing fat in isolation can lead to lower-face sagging. Facelifts and minimally invasive tightening procedures, like FaceTite, can help pick up the slack. Liposuction of the neck and jawline is another sometimes necessary supporting procedure. Without it, an aging jowl may suddenly steal the show: “It’s a compare/contrast issue,” says Dr. Sunder. “The jowl may appear to protrude more, once the area above it thins out.”

Related: Off-Label Is the New Black: The Weird New Ways Doctors Are Using Filler

One final note

For those of you wondering, as I was, if fat-dissolving Kybella might be a worthy competitor to buccal surgery: Nope. Doctors don’t recommend using the injectable in this nerve-rich region. As Dr. Nazarian explains, “Our nerves are all surrounded by a [protective sheath of] fat called myelin. And Kybella doesn’t differentiate between fat we don’t like and the myelin around our nerves. So if we hit a nerve, your smile might be off for six weeks or so, until the myelin regenerates.” Plus Kybella has become synonymous with major swelling and repeat treatments. With buccal surgery, patients swell just the once, she adds, “and then they’re happy and move on with their lives.”